The benign narrative of the beloved artist must be deconstructed, as she also embodies the US’s detrimental values.

Bryan Martin

January 19, 2026

— 5 min read

Bryan Martin

January 19, 2026

— 5 min read

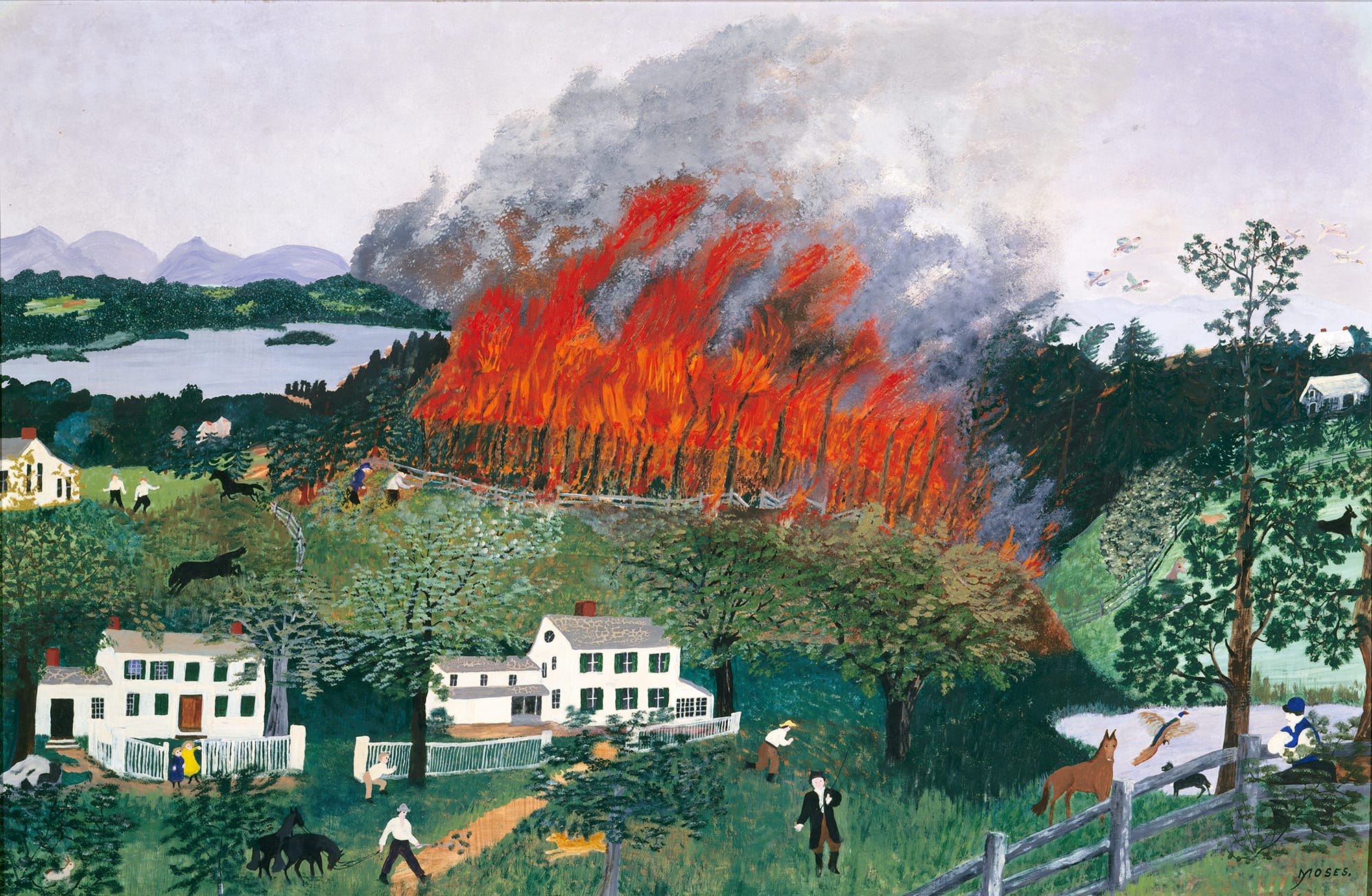

Anna Mary Robertson (Grandma) Moses, "A Fire in the Woods" (1947), oil on board (photo courtesy the Smithsonian American Art Museum)

Anna Mary Robertson (Grandma) Moses, "A Fire in the Woods" (1947), oil on board (photo courtesy the Smithsonian American Art Museum)

WASHINGTON, DC — The 2025 government shutdown delayed the opening of Grandma Moses: A Good Day’s Work at the Smithsonian American Art Museum by about a month. While the curatorial team can’t be faulted for this, it remained fresh on my mind as I considered the powers we are beholden to in the United States. The exhibition begins unexpectedly with a small selection of landscapes on fire or caught in an impending storm — moments of chaos not typically associated with the famed centenarian artist whose work harkened back to rural, idyllic depictions of the US during an era of rapid modernization.

The excitement these flames stirred in me was quickly extinguished by the exhibition’s safe presentation of Grandma Moses's work. Its main accomplishment is its scale, which allows visitors to enjoy an astounding quantity of this seminal artist’s oeuvre. But rather than presenting any novel or nuanced readings of the artist, or even justifying the exhibition’s evocative title, it lays out a thorough biography of the artist that is didactic as opposed to substantial.

This lack of discursive rigor is disappointing, given that the exhibition catalog brims with wonderfully researched essays that complicate the scholarship on Moses. While it’s easy — and true — to point to Trump’s executive order “Restoring Truth and Sanity to American History” as the reason for this risk-averse approach, the discrepancy reveals a deeper issue: the costs of preserving the myths that embody US exceptionalism. Grandma Moses’s trajectory as arguably the most famous artist in the United States is certainly notable; however, her vast, complex body of work warrants more careful aesthetic critique. The seemingly benign narrative presented in the galleries must be deconstructed, as it also embodies detrimental values the United States holds.

Grandma Moses, "Early Springtime on the Farm" (1945), oil on high-density fiberboard

Grandma Moses, "Early Springtime on the Farm" (1945), oil on high-density fiberboard Anna Mary Robertson Moses was born in 1860 in the farmland of Washington County, New York. She was briefly educated in a one-room schoolhouse and then sent to work full-time for a wealthy couple as a preteen. Through that difficult experience, Moses learned skills in domestic farm labor that she would carry to Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley after marrying her husband, Thomas Salmon Moses, as they tried to make a fortune in the Reconstruction-era South. Although they founded a life there, having 10 children, 5 of whom survived to adulthood, Moses and her family eventually moved back to Upstate New York after 18 years in 1905, where they bought a small, successful farm. In 1938, Moses was discovered by Louis Caldor, an art collector who saw her paintings in a drugstore. She gradually entered the limelight, becoming an endearing figure who graced the cover of Time magazine and whose work was reproduced in memorabilia, making her a ubiquitous grandmother figure.

While Moses’s age is often pointed out biographically in the show, it is never given credence as an artistic factor, despite its formal importance to her painting. In fact, it was the impetus for her artistic output, as she switched from crafting pictures out of yarn to painting because of rheumatoid arthritis. In her catalog essay, “Age, Race, and Memory,” Erika Doss articulates that the increase in life expectancy in the 20th century marginalized older Americans, leading to false perceptions that they were burdens on their families and society. Doss then frames Moses as the antithesis: a symbol of the strong, self-sufficient American spirit.

Grandma Moses, "White Birches" (1961), oil on pressed wood

Grandma Moses, "White Birches" (1961), oil on pressed woodMoses’s age manifests in ways that are never acknowledged in the exhibition, though. Made 16 years apart and displayed side-by-side, “Early Springtime on the Farm” (1945) and “White Birches” (1961) evidence the deterioration of the artist’s fine motor skills. The springtime scene, still covered in a blanket of snow, is made up of bold, controlled applications of paint, while the green, vivacious scene surrounding nine birches has a soft, splotchy, expressionistic quality that suggests a loss of technical dexterity. Rather than exploring the reality of old age changing our bodies, the show and catalog reinforce the notion of Moses as a figure who beat time. The artist still experienced the effects of aging, and the omission perpetuates the idea that any bodily flaws are a burden to society — a larger ableist tendency prevalent in the United States.

The exclusive presence of White figures in Moses’s scenes on display is another issue that the exhibition skirts. The racial bias is especially evident when considering her depictions of Virginia, where she is known to have hired Black domestic and farm laborers for years. “Calhoun” (1955), for instance, depicts a beautiful brick farmhouse and surrounding fertile farmland happily tended by White workers, betraying the historical reality. The artist herself never publicly acknowledged this disparity, and although the show references the “predominantly light-skinned” subjects, that is the extent of its critical analysis. Several essays in the catalog do tackle the issue of the racial dynamics of land ownership in the South, yet the absence is glaring in the galleries.

Grandma Moses, "Calhoun" (1955), oil on pressed wood

Grandma Moses, "Calhoun" (1955), oil on pressed woodIronically, race is also tied to the weakest part of Moses’s practice: painting figures. Moses’s amorphous people, with crude smiley-face lines as expression, often detract from her skillfully rendered, serene landscapes. The quality of Moses's work as a painter has always been central to the artist’s discourse: “Serious” formalist critics of the 20th century derided her work for perceived fluffiness and its inconsequentiality to Modernism, while populists believed her achievements to be extraordinary. Why can’t both be true? Many of Moses’s paintings are formally spectacular, but aesthetically unpleasant flaws plague others. Take “July Fourth” (1951), which shows a White community parading down a town’s main road, waving flags as a group of kids play baseball under another flag. The mass of figures amplifies how awkward the faces, with their black dots and lines, are. Both this and the nationalism are cloying, lacking the poise of Moses’s more sparse and contemplative scenes.

Grandma Moses: A Good Day’s Work feels frozen in time. While the catalog does admirable heavy lifting, it’s a massive disservice to both a public familiar and unfamiliar with her rich history to offer a show with little new. The most unfortunate part of the show is that refusing to complicate her legacy actually flattens it. Instead, more profound truths can be uncovered within her work to debunk harmful mythologies endemic to the US, while still upholding the magnitude of Moses’s achievement as one of the most famous and delightful American artists.

Grandma Moses: A Good Day’s Work continues at the Smithsonian American Art Museum (G Street Northwest & 8th Street Northwest, Washington, DC) through July 12. The exhibition travels to the Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art in Bentonville, Arkansas, from September 12, 2026–March 29, 2027. It was organized by Leslie Umberger and Randall R. Griffey with Maria R. Eipert.