The artist paints the distance between the homeland you lose and the one you try to dream back into existence.

Qingyuan Deng

January 19, 2026

— 4 min read

Qingyuan Deng

January 19, 2026

— 4 min read

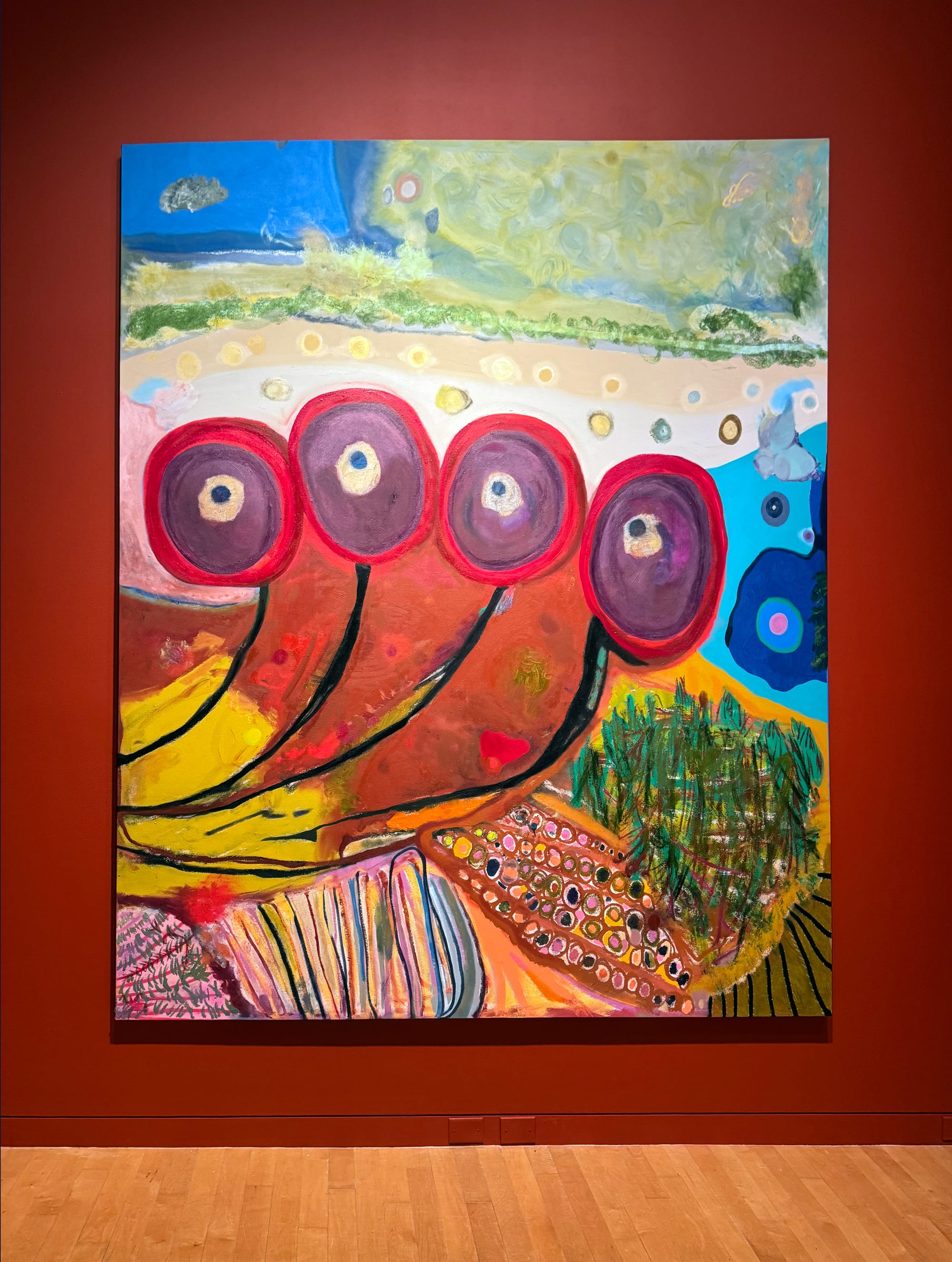

Uman, "first class, window seat" (2025), acrylic, oil, oil stick on canvas (photo ©Uman; image courtesy the artist, Nicola Vassell Gallery, and Hauser & Wirth; all other photos Qingyuan Deng/Hyperallergic)

Uman, "first class, window seat" (2025), acrylic, oil, oil stick on canvas (photo ©Uman; image courtesy the artist, Nicola Vassell Gallery, and Hauser & Wirth; all other photos Qingyuan Deng/Hyperallergic)

RIDGEFIELD, Conn. — Walking into Uman: After all the things… at the Aldrich, the first thing I noticed was that all the works appeared to be floating and unfixed, ready to occupy other literal or metaphorical positions. In the side gallery, black and white dots drift across the walls, orbiting “and it’s the thing again” (2025) and “ayoyo’s warmness” (2025) like dust motes or scattering seeds. The former, a painting of a creature with a black snakelike body, a white circular head, and a bright orange eye against frantic red and yellow marks, formally echoes the nearby “the thing #1” (2023), a sculpture of a streetlight springing out of a mound of soil, its body marked with a knotted silk scarf that seems to suggest anthropomorphism. In the latter, red dots dance on geometrically divided zones of densely colored, largely monochrome blocks, evoking patterns of East African tapestry. A line of black tassels hangs from the painted linen, recalling the artist’s earlier years in the fashion world.

In this room, other smaller works extend that sense of fluidity with quick, brutish charm. Blunt, almost childish brushstrokes, made without any evidence of hesitation, create free forms vaguely recognizable — the tilt of a house’s roof, the triangular silhouette of a mountain, the circle of a sun. A line lunges, reverses, and turns into a wing; a smear of green and blue pushes against a fog of pink; orange orbs hover as if arranged by chance. Rather than posturing toward an encrypted biography, these works turn outward, as if capturing and sharing a slippery memory before it evaporates. The paintings’ red borders — soft, hazy, sometimes glowing — give the impression of aura or heat, the emotional fringe of an image distantly recalled rather than observed. For Uman, images don’t hold still. They are expressions of restless meanings, always slipping into other territories moments later.

Uman, "and it’s the thing again" (2025), acrylic, enamel, oil, and oil stick on canvas

Uman, "and it’s the thing again" (2025), acrylic, enamel, oil, and oil stick on canvasUman’s looping, colliding marks build toward a messiness that feels both impulsive and deliberate, but the paintings never chase virtuosity, sidestepping the sense of transcendence promised by abstract artists like Rothko. It doesn’t feel like she is painting toward escape, but rather toward the world as she carries it: the irrevocable loss of childhood Somalia; the landscapes of Upstate New York that both recall and forestall that original home, performing both delights and failures; and private interior terrains. These paintings suggest to me finding home in places far from the land that first formed her.

In “melancholia in a snowy walk” (2025), for instance, a field of spiraling curls and morphing spines form a swirling pastoral scene that feels nearly cosmic. It, along other larger canvases, is installed against deep red walls that infuse the room with a primordial atmosphere that seems to expand the smaller works’ searching energy into vast, surreal compositions. In “first class, window seat” (2025), wavy grids ripple and bend, behaving like an ecstatic meadow of primal colors and suggesting woven textiles, irrigated fields, and the impossible geometry stitching together a life across continents. Up close, stars and cells emerge but never cohere into a realist observation. “melancholia in a fall breeze” (2025) turns fully toward dream logic, immediate yet also mysterious: Pink tides rise beside fluctuating planets. Red circles congregate and reproduce wildly. A wheel-like form glows with neon precision. In “amazing grace glorious morning” (2025), four red circular forms bloom in a row. Are they drums, fruits, or breasts? Nothing is literal, but everything feels inhabited, longingly reconstructed from art-historical fragments, stories, and inherited memories.

Across the exhibition, Uman’s symbols remain deliberately opaque. Circles, spirals, arrows, and nests of marks flirt with legibility but refuse translation. That refusal feels not like coyness, but protection — keeping the complexity of diasporic experience intact, unflattened, and unclaimed. Ultimately, what lingers is how these paintings inhabit the space between recognition and estrangement. A sun looks like an eye. A hill looks like a shoulder. A memory looks like weather. Uman paints the distance between the homeland one loses and the homeland one tries, again and again, to dream back into existence. In her hands, abstraction becomes not an escape from history but a vessel for carrying what official records refuse or cannot speak aloud.

Uman, "melancholia in a snowy walk" (2025), acrylic, oil, oil stick on canvas

Uman, "melancholia in a snowy walk" (2025), acrylic, oil, oil stick on canvas Uman, "amazing grace glorious morning" (2025), acrylic, oil, oil stick on canvas

Uman, "amazing grace glorious morning" (2025), acrylic, oil, oil stick on canvas Uman, "ayoyo’s warmness" (2025), oil, oil stick, and mixed media on linen

Uman, "ayoyo’s warmness" (2025), oil, oil stick, and mixed media on linen Uman, "diamonds in the sky" (2024–25), acrylic, enamel, oil, and oil stick on canvas

Uman, "diamonds in the sky" (2024–25), acrylic, enamel, oil, and oil stick on canvas Uman, "tear it all up" (2024–25), acrylic, enamel, oil, and oil stick on canvas

Uman, "tear it all up" (2024–25), acrylic, enamel, oil, and oil stick on canvasUman: After all the things ... continues at the Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum (258 Main Street, Ridgefield, Connecticut), through May 10. The exhibition was curated by Amy Smith-Stewart.